But our children are immersed in a heavily gendered world.

The brain is a blank canvas when it is created.

What the research says...

Modern neuroscientists have identified no decisive, category-defining differences between the brains of men and women.1The idea that differences between boys and girls are biological and cannot be changed has been discredited.2

Instead, it should be acknowledged that the relationship between the brain and its world is a constant two-way flow of traffic and we need to pay as much attention to what is going on outside our heads as well as inside.3

1. Rippon, G. (2019). The Gendered Brain, Bodley Head: London.

2. Fine, C. (2011). Delusions of Gender: the real science behind sex differences, Icon Books: London.

3. Ibid (n 1).

- A review of dozens of gender-disguise studies shows adults rating babies’ expressions and physical appearances differently based on the sex they believed the babies to be. Adults also tend to choose different toys for each sex, footballs and hammers for babies believed to be boys, dolls and hairbrushes for those they believe to be girls. They also engage with them differently – in a more physical way with boys and more verbal ways with girls.1

- Analysis of the most popular children’s books in 2018 showed that male characters dominated and that a child is seven times more likely to read a story that has a male villain in it than a female baddie.2

- Almost three times as many STEM toys were found to be advertised as for boys than girls.3

- In toy catalogues, girls were 12 times more likely to be shown playing with baby dolls, while boys were 4 times as likely to be shown playing with cars. Of the children shown with guns and war toys, 97% were boys.4

1. Eliot, L. (2009). Pink Brain, Blue Brain: How small differences grow into troublesome gaps - and what we can do about it. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: New York.

3. The Institute of Engineering and Technology (2016). https://www.theiet.org/media/press-releases/press-releases-2016/06-december-2016-parents-retailers-and-search-engines-urged-to-re-think-the-pink-next-christmas/

4. Let Toys be Toys (2017). http://lettoysbetoys.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/LetToysBeToys-Catalogues-report-Dec17.pdf

From the clothes that they wear to the toys that they play with, this can limit children for the rest of their lives.

- Toys provide training opportunities. But because play with ‘masculine toys’ allow children to develop skills that ‘feminine toys’ do not, and vice versa, stereotypes may restrict development.1

- Certain clothes can limit physical movement. A study of 10-year-old children found girls did significantly less exercise when wearing a school dress than they did when wearing shorts.2

1. Eliot, L. (2018) ‘Impact of gender-typed toys on children’s neurological development’ in Weisgram, E. & Dinella, L. [eds] Gender typing of children’s toys: How early play experiences impact development. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association, pp 167-187.

2. Hannah N., et al., (2012) 'The effect of school uniform on incidental physical activity among 10-year-old children', Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 3:1, 51-63.

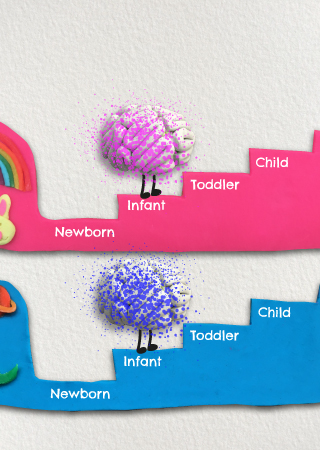

As they grow, brains pick up on social rules and learn what is “expected” of their gender.

- Typically before the age of two, children are conscious of the social relevance of gender.1

- By the age of 6, girls are less likely to believe that members of their gender are ‘really, really smart’. Girls also begin to shy away from novel activities said to be for children who are ‘really, really smart’.2

- At age 7, children’s career aspirations appear to be shaped and restricted by gender-specific ideas about certain jobs.3

1. Kane, E. W. (2006). “No Way My Boys Are Going to Be Like That!”: Parents’ Responses to Children’s Gender Nonconformity. Gender & Society, 20(2), 149–176.

2. Bian, L., et al., (2017). ‘Gender stereotypes about intellectual ability emerge early and influence children’s interests’, Science 355(6323), pp 389-391.

3. Chambers, N., et al., (2018). Drawing the Future survey. Education for Employers.

The effects can be harmful on their wellbeing and limit future opportunities.

- Children in friendship groups that emphasised traditional gender stereotypes - girls having nice clothes and boys being tough - had a lower overall wellbeing.1

- In classrooms where students believe that reading is a girls’ activity; boys showed less motivation, belief in their competence and poorer performance in reading-related tasks, while girls benefitted from this gender stereotype.2

- Girls are less likely than boys to aspire to science careers, even though a higher percentage of girls than boys rate science as their favourite subject. Girls who aspire to science and STEM careers tend to describe themselves as ‘not girly’.3

- Men who hold strong gender-stereotyped beliefs are at a higher risk of becoming violent towards partners.4

- Beliefs held about how boys and men should typically act are more restrictive than those for girls and women. It is thought women should be communal and avoid being dominant; while men should be agentic, independent, masculine in appearance and interested in science and technology, but avoid being weak, emotional, shy and feminine in appearance.5

1. The Children’s Society (2018).¸The Good Childhood Report 2018, Children’s Society: London.

2. Muntoni, F., et al., (2020) ‘Beware of Stereotypes: Are Classmates’ Stereotypes Associated With Students’ Reading Outcomes?’, Child Development.

3. Archer, L., et al., (2013) ASPIRES Young People’s Science and Career Aspirations, Age 10-14, King's College London, UK.

4. Reyes, H., et al., (2016) ‘Gender role attitudes and male adolescent dating violence perpetration: Normative beliefs as moderators’, Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(2).

5. Koenig A. M., (2018) 'Comparing Prescriptive and Descriptive Gender Stereotypes About Children, Adults, and the Elderly', Frontiers in psychology, 9, 1086.

But there's good news! The brain is malleable, and this effect can be reversed.

- Showing magazines to children with pictures of boys or girls playing with toys that are not typically related to their gender.1

- Allowing girls to read biographical stories of women in gender-atypical careers.2

- "Empowering" girls by enabling them to imagine themselves doing activities in positions of power.3

- By manipulating motivation, for example when women and men expect to get paid, they perform better at inferring what another person is thinking or feeling than those who do not expect payment. Gender differences disappear to reveal motivational differences instead.4

"We now know that, even in adulthood, our brains are continually being changed, not just by the education we receive, but also by the jobs that we do, the hobbies we have, the sports we play. The brain of a working London taxi driver will be different from that of a trainee and from that of a retired taxi driver." -Gina Rippon, The Gendered Brain

1. Spinner L, et al., (2018) Peer Toy Play as a Gateway to Children’s Gender Flexibility: The Effect of (Counter)Stereotypic Portrayals of Peers in Children’s Magazines. Sex Roles, 79(5), pp 314-328.

2. Nhundu, T.J., (2007) Mitigating Gender-typed Occupational Preferences of Zimbabwean Primary School Children: The Use of Biographical Sketches and Portrayals of Female Role Models. Sex Roles 56, pp 639–649.

3. Van Loo, K. J., et al., (2013) On the Experience of Feeling Powerful: Perceived Power Moderates the Effect of Stereotype Threat on Women's Math Performance. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 39, pp 387-400.

4. Klein, K. J. K., & Hodges, S. D., (2001) Gender Differences, Motivation, and Empathic Accuracy: When it Pays to Understand. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(6), pp 720–730.

Imagine if children could be whatever they wanted to be without stereotypes...

Created in partnership by:

and Mitra Abrahams

instagram.com/data_mitra

About Us

not only pink and blue is an online marketplace celebrating children being children and challenging the harmful stereotypes that can limit their aspirations and wellbeing. That's why you'll be able to search for children's clothes, books and toys by activity and attitude on not only pink and blue, and we also meet every Partner who we work with.

Mitra Abrahams is a freelance data analyst and visualiser. I aim to translate technical data into emotive and simple visualisations that everyone can digest. You can find more of my work on Instagram.